|

| The French Ministry of Justice, Paris |

French judge Jean-Michel Gentil

has filed preliminary charges of 'abuse of a person in an impaired state' against former president Nicolas Sarkozy. The charges relate to a €152,000 donation to his 2007 election campaign by Liliane Bettencourt, the ageing heiress of the sprawling L'Oréal cosmetics and beauty empire and the world's third-richest woman, with a net worth of €39 billion. Bettencourt, now aged 90, has been involved in a highly mediatised and long-running family feud over her fortune, and her failing mental health eventually led to her being put under judicial supervision at the request of family members.

Sarkozy entered the picture in 2008 when

it was revealed that Bettencourt's chief accountant had alleged to police investigators that the heiress had authorised the Sarkozy election campaign fund payment after meeting him in 2007. The accountant also said that Sarkozy had visited the Bettencourt home several times and that each time he left with a brown envelope containing banknotes.

His UMP political party's offices were subsequently raided by judges looking for evidence of wrong-doing, and the next two years saw many witness statements being taken, several people being charged with various related offences, and efforts by judges to access Sarkozy's bank accounts are ongoing.

The political reaction to the news was both instant and predictable. UMP politicians have embarked upon a virulent crusade against Gentil's decision, which is best summed up by former Sarkozy henchman Henri Guaino

who told an interviewer that the judge's decision was "irresponsible", that he had "dishonoured the institutions" as well as "[French] justice." The accusations, he said, were "grotesque...unsupportable...unbelievable...intolerable". Meanwhile, Hollande and his socialist government have wisely decided to refrain from seeking to gain cheap political capital from the affair. Mind you, they can hardly do otherwise seeing as Hollande has just had to fire his Budget minister, Jérôme Cahuzac, after the latter was put under official investigation by a judge earlier in the week in relation to accusations that he has ferreted what could be illegally gained money out of the country and into a Swiss and other bank accounts.

More importantly though - and in a clear sign that the Sarkozy affair is set to be a viciously fought battle between Sarkozy and Gentil -

it emerged yesterday that after being charged face to face by Gentil during the charge convocation the mood allegedly turned ugly, with Sarkozy leashing a veiled yet implicitly menacing threat, promising that "I'm going to take this matter further, make no mistake about it".

So the battle lines have been drawn. But these are no new battle lines, and there is no new front in the bitter and eternal war which has always pitted French presidents and other elites against a legal system which is doing no more than what is is mandated to do.

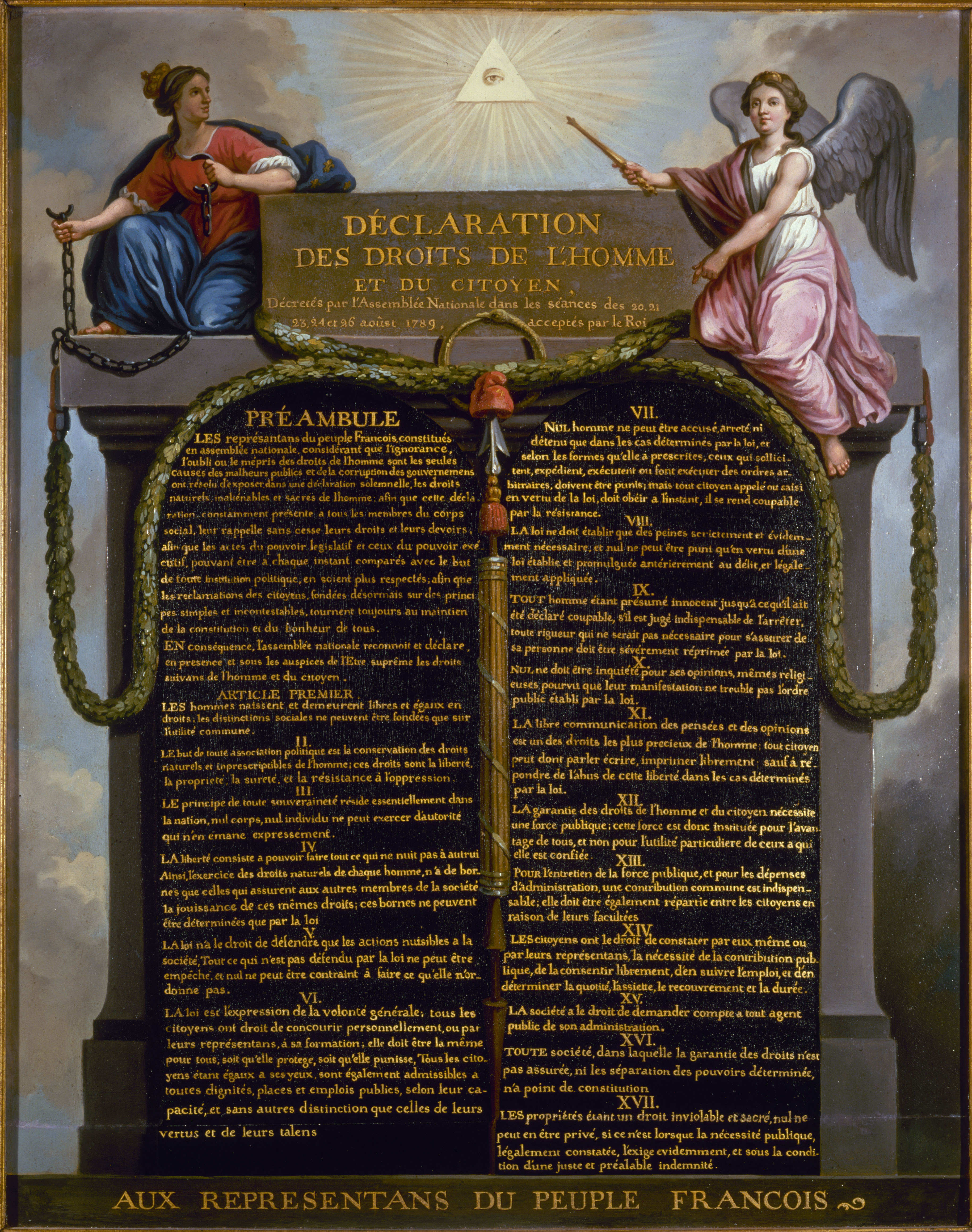

The unfettered independence of the French judicial system is enshrined within the French Constitution, but France is a country which is having many more problems putting the theory into practice than are many other western countries. Politicians and others in all countries try to influence their justice systems in one way or another, but the exceptionally porous nature of the relationship between the French justice system and political power is noteworthy.

Whereas it has not been uncommon in many other countries since the 70s to see politicians, including presidents and prime ministers, investigated and/or charged with alleged offences, and pay heavily for them, only one French president has ever been found guilty of an offence, with Jacques Chirac being handed down a 2-year suspended sentence for embezzling public funds after a trial which he did not attend due to illness.

There are two main reasons for this state of affairs, the first being that French presidents are immune from prosecution during their mandate. This means that they cannot be charged with alleged offences committed whilst in power until they are no longer president. And even if charges are eventually brought the French legal system permits endless legal challenges and procedurial objections to be lodged against charges as well as the possibility of endless appeals. The result is that cases become heavily diluted over time, that which makes proving guilt very difficult.

The second reason is direct political interference in ongoing cases. Judges can be removed from a case if a president fears they may be getting uncomfortably close to the truth, and governments often refuse to hand over pertinent documents and other evidence to investigating judges. Nobody here will forget how Alain Juppe's Justice minister, Jacques Toubon, tried to force a prosecutor back to France from his holiday in the Himalayas in order to persuade him to drop a case against a political ally (Paris Mayor Jean Tiberi) which had been brought by his adjoint. Toubon even ordered a helicopter to fly him down from the mountains! The prosecutor refused on this occasion. Toubon is also known for having ordered police and prosecutors who were on their way to raid the offices of another political ally to search them for evidence of fraud to turn back. He was obeyed.

Also, several high-profile cases of a very sensitive nature involving presidents - including Sarkozy - have been deliberately bogged down by endless presidential foot-dragging. They include the Taiwan frigates case, involving kickbacks to political leaders in exchange for Taiwan's agreement to buy French frigates. This case also involves the highly suspicious deaths of several witnesses. Another case is the Karachi bombing, in which a dozen French engineers were killed in the city whilst doing highly sensitive work for the government on submarines. This case has never really got off the ground either.

Sarkozy went even further whilst in power. He removed a number of inconvenient magistrates and prosecutors and used his friendship with famous Parisian magistrate Philippe Courroye to ask him to refuse to name an investigating judge for the Bettancourt case, which was making too much progress for his comfort. Courroye obeyed, much to the anger of magistrates and judges alike, and the case was thus dragged out. Sarkozy then went on to quite simply eliminate the functions of examing magistrates, thus strengthening his hold on the justice system. Other legislation was also introduced that would attempt to weaken the justice system, to the point where even his political allies were becoming afraid of the consequences of such actions.

But Courroye eventually fell into disgrace for reasons relative to other cases he was handling, and the investigation eventually got back on track after the alleged Bettencourt payments hit the headlines. Gentil was finally put in charge of the case, his work now made easier because Sarkozy is no longer president, and Sarkozy has now been charged.

This affair and the many revelations of meddling in the justice system it has led to has debunked the myth of an independent justice system in France. Sarkozy's meddling is the straw which broke the camel's back, and his being charged represents a clear victory for the many honest magistrates, judges and others who are trying to do their job despite heavy political interference. They deserve respect for their perseverence and courage.

But don't count on further improvements anytime soon. François Hollande promised to repeal and remove the system of presidential immunity from prosection during his election campaign, but now that he is in power he and his advisors have backtracked. The project as it stands today would only remove immunity for a limited number of civil offences - i.e. extremely minor cases, and even then they would be difficult to prosecute - but immunity shall remain for embezzlement, fraud and other criminal offences, that which renders the legislation toothless.

France's magistrates and judges may have won a victory by charging Nicolas Sarkozy, but the war for judicial independence in France is far from being won.